Back in hazy 1991, in Cologne, I met a group of Belarusians from a charity helping children affected by the Chernobyl disaster, and they invited us to the USSR. We bought medicines and arranged for a team of German doctors to visit. I was pleasantly surprised by the warm welcome in Belarus and Russia. I knew, of course, what the Germans had done did to these lands during WWII and subconsciously expected a hostile, wary attitude. But my fears were totally unfounded.

Mamayev Kurgan in Volgograd (former Stalingrad)

Personal archiveWhat first struck me on arriving in Russia in 1991 were the bedroom suburbs. Almost all large Soviet cities, it turned out, were built this way, with arrays of residential buildings hugging the outskirts. It was on the journey there that I first took a close-up look at the map. In my mind’s eye, the USSR had always been a distant land, but now I saw that only 1,100 km separated Berlin from Minsk. Rome was twice as far away, and Madrid three times!

In public spaces, Russians are quite standoffish and rarely make eye contact. They often don't greet each other in the lobby of apartment blocks, which would be unimaginable in Germany. In public spaces, there is a prevailing struggle with the ingrained notion to expect nothing good from strangers or the state. Anything can happen, as they say, and often does. Bitter historical experience has taught many to rely only on themselves. But as you get acquainted more closely, as you move from the public to the personal space, the transformation is spectacular. It won't ever again cross your mind to say that Russia is a cold country!

Russians are quick to take offense, which I was completely unprepared for when I came here. Here it’s a particular form of social communication. It would be fair enough to say: If you want your feelings to be taken seriously in Russia, you have to get offended! Even at work. What’s more, Russians feel aggrieved about anything, not just criticism or lack of attention. It’s through this that people express their feelings. And you know what? I’m feeling aggrieved right now! At first I did it consciously, but now I catch myself thinking I’m no longer in control of these feelings.

Friends say I’m Russified. What does that mean exactly? How does it manifest itself? When I start cussing to myself, I use Russian swear words, known as mat [cursing]. You know, it’s simply not possible to swear as much in German as in Russian. German expletives are tame compared to Russian ones. If you want to swear for real, learn Russian mat!

My wife is Russian, and we discovered that my past life in Germany was not 100% German, and likewise her Moscow existence had European elements. For example, now I can’t do without bread at the table. In Germany, it’s served only for breakfast or dinner, very rare with hot dishes. In Russia, bread is ubiquitous. And I’ve taken to Russian drinking culture. For example, I can’t drink without a toast. In Germany, people often start drinking as soon as their glass is filled. Here, the toast creates a special bond between everyone at the table.

I live in Moscow, but don’t like it. The city is impossible to love, it’s just too big, noisy, aggressive, and forever changing. Grow fond of something, and the next day it’s different. Like many Western Europeans, I prefer St. Petersburg. It’s a city of dreams, not reality, created by one man’s vision.

Foreigners in Russia need to realize that English will be of little use, both in everyday matters and getting to know the country. Language has all the answers – without it your access to Russia will be severely limited. For example, the word obida (“offense”), which we touched upon above. In Russian, it has more shades of meaning than in English or German, and sometimes it’s hard to find an exact equivalent.

For example, the expression Mnye za derzhavu obidno from the movie White Sun of the Desert (which, by the way, I advise all foreigners to watch). How do you say that in English, for example? The literal translation is, “I’m offended on behalf of the country/state/realm” or “It pains me to see the nation suffer so,” but the pain runs deeper in Russian. Also, Russian has two words for “truth”: pravda (man’s truth, which may not actually be true) and istina (God’s truth, which is eternal – and can be rendered in elevated English as “verity”). Or the word zanuda, which means either “bore” or “pain in the you-know-what,” but isn’t quite either of those. Sure, there are plenty of examples in the opposite direction, too.

READ MORE: 10 Russian words impossible to translate into English

It’s often said that Russian is hard to learn. That’s not quite the case. You need to treat the learning process not as a continuum, but as a sine wave with all its ups and downs. Sometimes there’s no progress, and then suddenly a leap forward. I remember how I grappled with adverbial participles. It was a eureka moment when I got it. Such an elegant and precise way to express your thoughts! The main thing is never give up.

I’ve lived in Russia for more than a quarter-century and often get asked why I don't come back to Germany. There’s one reason: the people. My wife, friends, loved ones. To be honest, I’ve got no relation to Russia. Only to certain individuals. And to politics as well.

Everyone talks about the “mysterious Russian soul,” but there’s no such thing! You could just as easily talk about the German, French soul, etc. People in any country have their own national traits and different mentalities. The term “Russian soul” averages out and blunts the complexity and diversity of the Russian people. It’s like giving the average temperature over the year without mentioning the extremes.

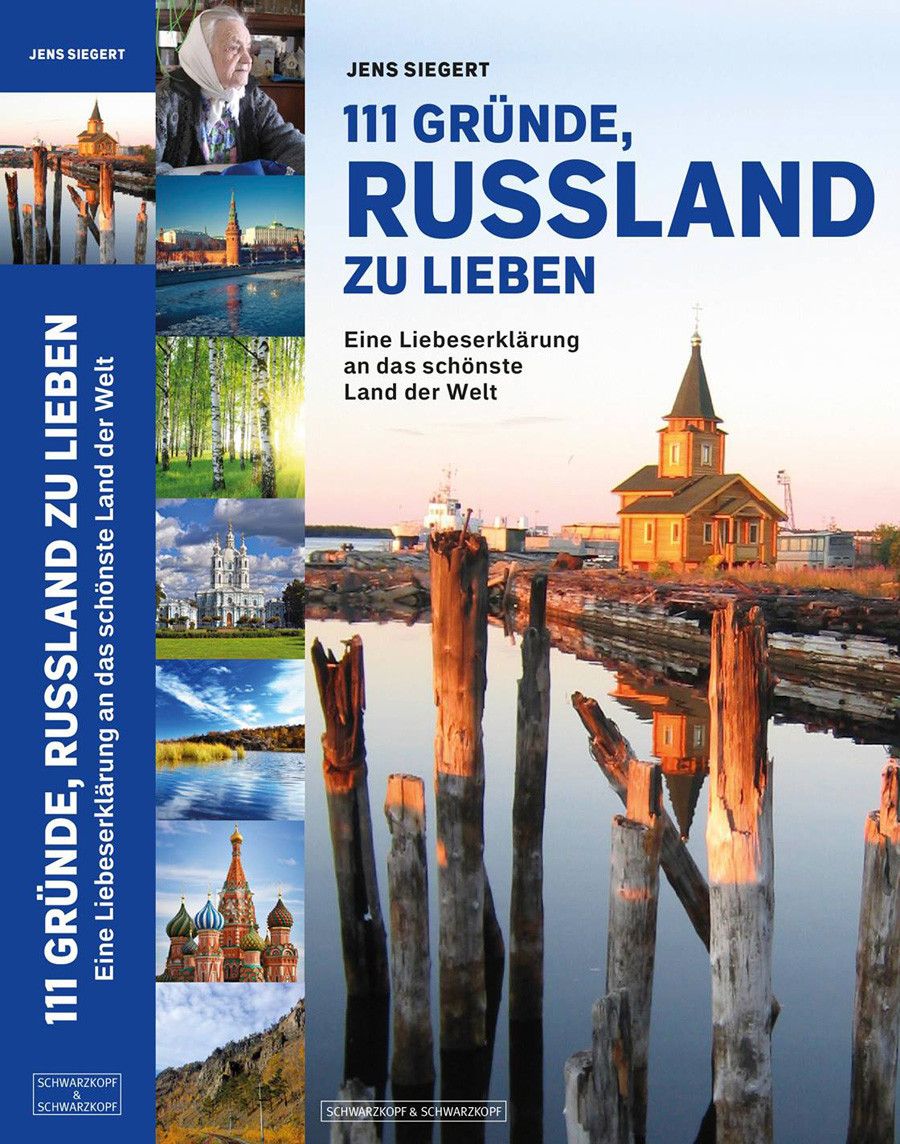

Over in Germany, I recently published the book111 Reasons to Love Russia. It’s my attempt to explain Russia to the Germans, using 111 strokes to paint a general picture. In it, I discuss recipes, movies, the Bible, phenomena like the criminal world and living “by the unwritten rules” (po ponyatiyam, as they say), and the “person-state” dynamic—the relationship between the individual and the powers that be.

I start the book with two chapters: “I love Russia because it is so homogeneous” and “I love Russia because it is so diverse.” This is not a contradiction. In Altai and Moscow, people speak the same language. In Germany, travel 20-30km down the road and the locals will be nattering away in a different dialect, surrounded by different architecture and sometimes even different food.

READ MORE: Can Russians from different parts of the country understand each other?

In this sense, Russia is very homogeneous. Yet at the same time, this vast land is home to more than 180 nationalities, it has tundra and near-subtropical climes. It is through this diversity and homogeneity that the country’s national features manifest themselves.

Inteview by Daria Aminova, translated from Russian.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox